The AI We Trust vs. The AI We Fear: Drones at the Crossroads

In November 2025, a Japanese woman married an AI chatbot—a digital partner who knew her deepest thoughts and provided unwavering emotional support. Millions didn’t find it strange. They’re already trusting AI with their hearts, their money, their health, and their lives on the road.

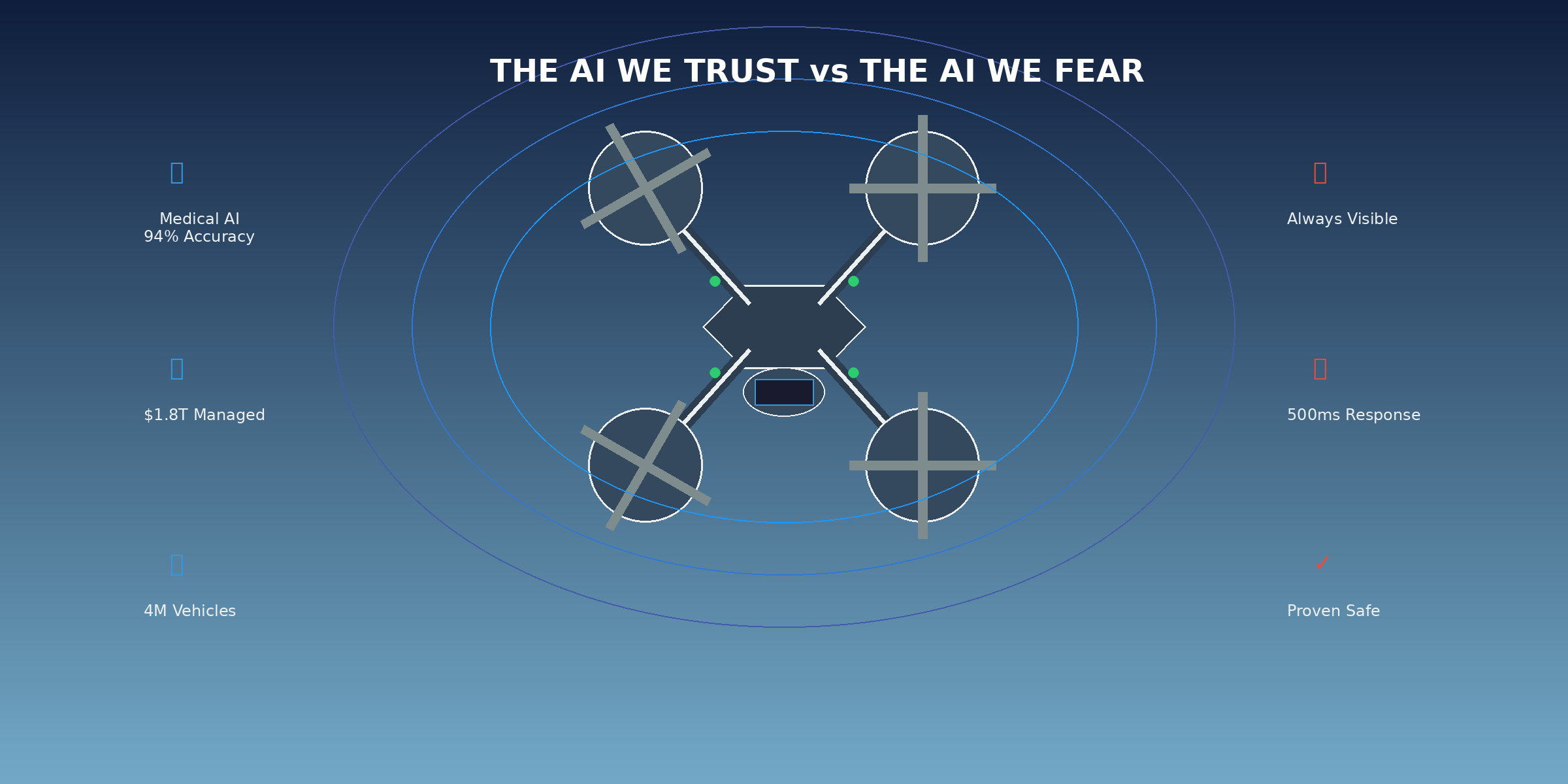

Yet when a commercial drone operator requests Beyond Visual Line of Sight operations with AI-assisted navigation—technology less complex than what’s controlling cancer diagnoses and managing billions in investments—regulatory agencies hesitate. The public erupts about “privacy” and “safety.” The cognitive dissonance is staggering. We trust AI to detect tumors radiologists miss, manage retirement savings, and control two-ton vehicles with our children inside—but we can’t trust it to fly a 15-kilogram aircraft? The fear isn’t rooted in capability. It’s rooted in the fact that we can see the drone.

The AI You Already Trust With Your Life

If you’re reading this in 2025, you’re already trusting AI with decisions far more consequential than drone operations. Harvard Medical School’s CHIEF AI achieved 94% accuracy detecting cancer across 19 types, outperforming current approaches by up to 36%. The LYNA system diagnoses metastatic cancer with 99% accuracy, catching tiny metastases human pathologists miss. AI-assisted breast cancer screening improves detection rates by 22%. These aren’t experiments—these systems are making life-or-death determinations in hospitals right now.

Robo-advisors managed $1.8 trillion globally in 2024. Vanguard’s Digital Advisor alone manages over $206 billion. These systems make complex portfolio decisions, execute trades, and rebalance assets with minimal human oversight—managing people’s retirement savings and financial futures.

Tesla has 4 million vehicles with Autopilot and Full Self-Driving features actively learning from real-world data. The system processes sensors, predicts collisions, makes split-second steering and braking decisions at highway speeds. Tesla reports one crash per 6-8 million miles with Autopilot versus the U.S. average of one per 670,000 miles. Waymo operates 2,000 robotaxis executing 14.7 million autonomous miles daily with 400,000 active users. You trust these systems with your life. You just don’t think about it because they operate invisibly.

The Drone Paradox: Seeing is Fearing

Modern commercial drones pack AI-powered collision avoidance, GPS-denied navigation, real-time LiDAR obstacle detection, and automated return-to-home. The DJI Phantom 4 (2016) reduced collision rates 30-50% with vision systems detecting obstacles at 15 meters and creating real-time 3D maps. By 2018, 70% of professional drones included obstacle avoidance. Current systems process environmental data and execute collision avoidance within 500 milliseconds—faster than human reaction time.

Yet Transport Canada’s Level 1 Complex BVLOS operations (introduced November 2025) still require visual observers despite technological capability for full autonomy. Why? Because you can see the drone. The AI managing your cancer diagnosis operates invisibly in hospital servers. The robo-advisor works in data centers you’ll never visit. Tesla’s self-driving activates seamlessly. But a drone? You look up and there it is—visible, mechanical, above you. And suddenly, all bets are off. The gap isn’t technological. It’s visibility bias.

What the Data Actually Shows

Between 2005 and 2016, 355 drone incidents in Canadian airspace showed 80.4% occurred above 400 feet AGL—the legal altitude limit. This isn’t technology failure. It’s humans breaking regulations. The famous 2017 Quebec City collision between a drone and King Air? Minor damage, no injuries. Investigation concluded: operator wasn’t following regulations. No authorization, operating in controlled airspace illegally.

Traditional aviation’s 2024 accident rate: 3.0 per 100,000 movements. NASA research on TSB accidents (1996-2003) found the majority attributed to human error. The pattern is consistent: humans are the weak link. Yet when discussing autonomous drones, we ask “what if the AI fails?” Nobody asks this about cancer diagnosis AI, investment algorithms, or self-driving features. Why? Because we don’t watch them work.

The Trust We Extend and Withhold

We’re not evaluating drone AI on capabilities or safety records. We’re evaluating it on psychological comfort with visibility. And that’s fundamentally irrational. Only 13% of Americans trust self-driving cars, yet Tesla has 4 million vehicles using autonomous features and Waymo serves 400,000 daily users. The gap between stated trust and actual usage reveals our real preference: we’ll use valuable technology regardless of stated concerns.

AI companions prove this starkly. MIT research found 25% of users form relationships with chatbots unintentionally—emotional intelligence is sophisticated enough that bonds develop naturally. Replika has 25 million users, Snapchat’s My AI has 150 million, and 72% of American teenagers use AI companions. A 2025 survey found 28% of American adults had romantic or intimate AI relationships. We trust AI with emotional well-being and mental health. But autonomous drones overhead? Terrifying. This isn’t safety calculation. It’s visibility bias.

The Path Forward

For Canadian operators, this irrational trust gap creates an impossible situation. You have technology capable of safer operations than human pilots alone. You have regulatory frameworks acknowledging this. But you’re fighting public perception unrelated to your safety record.

The operators who succeed won’t fight against AI capabilities. They’ll lean into them with professional training emphasizing AI partnership, not replacement. When you understand how obstacle avoidance works, interpret what AI is telling you, and know when to override versus trust completely, you become more capable than either human or AI alone. Clarion Drone Academy trains operators for this reality—preparing pilots to partner with sophisticated automation. Because AI-assisted drone operations are the only path forward for complex commercial missions.

We need to stop pretending this is about safety. If it were, we’d demand autonomous drones immediately—the data shows AI outperforms humans in obstacle detection, collision avoidance, and procedural compliance. But it’s not about safety. It’s about visibility and control illusion. We’re comfortable with AI making life-or-death medical decisions because we can’t see the algorithm. We’re comfortable with AI managing money because transactions happen in background. We’re comfortable with AI driving because the steering wheel maintains psychological control illusion.

Drones force us to confront what we’ve already accepted everywhere else: we trust AI with consequential decisions. The difference is that with drones, we have to watch it happen. Transport Canada’s cautious BVLOS approach reflects public discomfort more than safety concerns. The irony? Delaying AI-assisted drone operations actually reduces safety. Human pilots make mistakes, get fatigued, can’t process sensor data as quickly. By insisting on human oversight of operations AI could handle autonomously, we’re introducing the weakest link back into the safety chain.

The drone industry’s challenge isn’t convincing people to trust AI—they already trust it with hearts, money, health, and lives. The challenge is convincing them to trust AI they can see. For Canadian operators, professional excellence in AI-assisted operations isn’t optional—it’s existential. Every safe BVLOS flight builds the public trust regulatory frameworks need. The technology is ready. The regulations are evolving. What remains is building public comfort with the visible manifestation of what we’ve already accepted invisibly. The AI we trust with our lives is the same AI we fear in our skies. That contradiction won’t resolve through better technology. It will resolve through transparency, professional competence, and recognizing that the drone overhead uses the same AI systems we’ve trusted with everything else. The only difference: this time, we have to watch it work.